My Son Sent Me A Box Of Handmade Cookies For My Birthday. The Next Day, He Called & Said, “So, How Were The Cookies?”

I Said, “Oh, I Gave Them To Your MIL. She Loves Sweets.” He Went Silent For A Moment, Then Shouted, “You Did What?!”

I never expected a birthday gift from my estranged son to nearly end in tragedy. When I gave away the cookies he sent me, I thought I was sharing something sweet.

Sixty‑three doesn’t feel like anything, really.

It’s not a milestone. It’s not a round number.

It just sounds tired.

I spent the morning like I always do in Ohio.

Black coffee, the crossword, the creak of the porch swing under me, and a view of a lawn that refuses to stay green no matter how much I water it. A pickup rolled past with a small U.S. flag on the antenna, and somewhere down the block a radio murmured local news and baseball scores. It was quiet, comfortable in that lonely kind of way I’ve gotten used to since Ezra stopped speaking to me.

Then came the knock. Not the impatient tap of the mail carrier or the neighbor kid selling coupon books. Just one knock, then the sound of footsteps retreating.

I opened the door and saw the box—plain brown paper, carefully taped, a thin blue ribbon tied once around the middle. There was no doubt about the handwriting. I hadn’t seen it in three years, but I would have known it with my eyes closed. Ezra wrote like a blueprint. Precise. No wasted curves. Always in blue ink.

I didn’t open it right away. I just stood there barefoot on the doormat, staring at the neat letters spelling out my name:

Marlene Greaves.

I whispered it under my breath like it might sound different somehow coming from him.

Back inside, I set the package on the kitchen table. The coffee had gone cold. I reheated it and sat down, folding my hands in my lap like I was waiting to be called on. After three years of silence—no card when I had pneumonia, not a word when my sister passed away—now this.

Eventually, curiosity won. Inside the paper was a white box, and inside that, nestled in tissue like they were fragile, were cookies. Dozens of them, carefully iced, each one different: blue flowers, golden leaves, stars with sugar dust—all handmade. Butter and vanilla still clung to the tissue. Ezra had never baked a day in his life. No note, except a small card taped to the inside of the lid:

Happy Birthday, Mom. Let’s start over.

I held the card like it might vanish if I blinked. My throat tightened. Not quite a lump—just that soft ache that creeps in when you want something to be real but don’t trust it yet. Hope is noisy when you’ve taught yourself to live without it.

I didn’t eat them. I wanted to, but I didn’t.

Maybe it was pride. Maybe it was fear. Or maybe it was something quieter—something I couldn’t name but didn’t want to ignore.

I slipped one cookie into a small Tupperware container, sealed it, and placed it in the fridge. The rest I rewrapped carefully.

Ruth Langford lived just fifteen minutes away—Ezra’s mother‑in‑law. She’d always been good to me, especially when Ezra grew distant. I figured if anyone deserved something sweet, it was her, and it felt easier to give them away than to wonder what they meant.

That afternoon, I drove over. The sun was low enough to cast that soft orange light across the trees, and her wind chimes were already dancing. The doormat said WELCOME Y’ALL in weathered paint. I handed her the box with a smile, brushing off her protests.

Later at home, I stood in the doorway looking at the empty spot on the table where the package had been and tried not to feel relieved that it was gone. Relief can look a lot like cowardice if you stare at it too long.

The next morning, just as I was pouring coffee, the phone rang. The sound startled me. It’s been a long time since anyone called this early, and longer still since that number flashed across the screen.

Ezra.

I didn’t answer right away. My hand hovered over the phone like it might burn me. The call buzzed once more before I picked up.

“Hello.”

“Hi, Mom.”

His voice—smooth and casual—slipped through the line like nothing had happened. Like three years of silence hadn’t settled between us like sediment.

“Happy birthday. A little late, I know.”

“Ezra.” I sat down slowly, gripping the mug with both hands. “I got your package.”

“Yeah.” A soft chuckle. “I wasn’t sure you would. I wasn’t sure you’d open it, honestly.”

“I did. It was… unexpected.”

There was a beat of silence. Then he asked, a little too casually:

“So, how were they?”

“The cookies.”

“Yeah.”

I took a breath. “Oh, I didn’t eat them. I gave them to Ruth.”

The line went dead quiet. I pulled the phone away from my ear to check if the call had dropped. It hadn’t.

“You gave them to Ruth.” His voice was different now. Sharper. The warmth evaporated.

“Yes,” I said slowly. “She’s always loved sweets. And I—well, I didn’t know what to do with them.”

He didn’t speak for a long moment. I could hear his breathing—tight and uneven—then, quietly at first, but with building force:

“You did what?”

The words hit like a slap.

I blinked, stunned. “I—Ezra, what’s wrong?”

“They weren’t for her,” he said, clipped. “They were for you. Only you.”

His voice cracked—not with sadness, but something else. Frustration, maybe even panic. I couldn’t tell. A drawer slid somewhere on his end of the line. I pictured him in that spotless kitchen, lined up spice jars like soldiers.

I sat frozen, the coffee cooling in my hands. “I didn’t know,” I said, my voice small.

“Right. Of course you didn’t.” The bitterness bled through, thick and choking. “You never do.”

He hung up before I could say anything else.

The dial tone hummed in my ear. I set the phone down slowly, staring at the counter. My heart thudded in my chest—not fast, but deep, like it wanted to be heard.

Only you. That’s what he’d said.

I stood, walked to the fridge, and opened it. The small container was still there—one perfect cookie, untouched. I shut the fridge and leaned against the counter, suddenly cold.

That’s when the other phone rang—the landline in the hallway. Almost no one used it anymore. I walked toward it, dread already spreading.

The landline crackled when I picked it up, like the receiver had forgotten how to carry a voice.

“Marlene,” it was Laya—Ezra’s wife.

“Yes.”

Her voice was strained, brittle. “It’s Ruth. She’s in the hospital.”

I sat down without meaning to. “What happened?”

“She collapsed this morning. Nausea, disoriented. I thought it was the flu, but it got worse. She couldn’t stand. She was confused. The ER says they can’t find anything definitive. They’re running tests now.”

My mouth went dry. “Did she eat anything unusual?”

A pause. “She mentioned cookies. Said you brought them over.”

“I did. I gave her the box Ezra sent me.”

Laya didn’t speak. I could hear hospital noises in the background—monitors, heels on tile, a cart squeaking down a hall, a voice over the intercom paging a physician. Somewhere, the Stars and Stripes hung in the waiting area with a brochure rack beneath it.

“Do you think they could have made her sick?” she finally asked.

I swallowed. “I don’t know. I didn’t eat any myself.”

Another silence. “If you think of anything—anything at all—you’ll tell me.”

“Yes,” I whispered. “Of course.”

We hung up, and I sat there in the dim light, staring at the wall. The afternoon sun had faded and left the living room in a dull haze. I didn’t turn on the lights. I didn’t move for a long time. A siren wailed far off on County Road 7 and then was gone.

Later, after dark, I wandered into the kitchen with the aimless instinct of someone looking for order. I started cleaning, wiping down surfaces, folding towels that didn’t need folding. I opened the trash to empty it and saw something near the bottom: a small clear plastic bottle, like the kind vitamins come in. No label, just a faint ring of white powder clinging to the inside wall.

I reached in and picked it up, turning it in my hands. It wasn’t mine. I hadn’t seen it before. The cap was still screwed on tight.

I opened the fridge. The cookie was still there, tucked into its little container like it had been waiting for this moment. My hands shook as I lifted it out. I hadn’t even remembered why I saved it. Something sweet for later. A small kindness for myself.

Now I couldn’t look at it without feeling sick.

I carried the cookie and the empty bottle into the study and set them on the desk. The lamplight made the sugar crystals sparkle faintly. I sat down and folded my hands, staring at both like they might blink first.

Was I the target? Was it meant for me?

The questions hung there—too big to touch.

Later, just before bed, I called the lab where Janelle Morrow worked. She owed me a favor. I didn’t say much—just that I needed something tested quietly. She said she could meet me in the morning.

I hung up the phone and stood in the middle of the room for a long time before turning out the light. In the quiet, I could still hear Ezra’s voice in my head.

You did what?

The cookie stayed in the fridge that night. So did the dread.

The lab sat behind a medical office complex on the edge of town, the kind of place you’d never notice unless you were looking for it. Janelle came out herself to meet me in the parking lot, her lab coat too crisp for how early it was. She didn’t ask many questions—just raised an eyebrow when I handed her the container.

“This the kind of favor I’ll regret?” she asked lightly.

I tried to smile, but couldn’t quite make it land. “Just tell me what’s in it.”

She nodded and disappeared through the side door.

I sat in my car with the engine running and the radio off. My hands were cold. I didn’t drive away. I couldn’t.

Memories crept in like water under a door: Ezra at eight, folding napkins at the dinner table with sharp geometric precision. Ezra at ten, throwing a fit when I rearranged the pantry by color instead of size. Ezra at twelve, refusing to speak to me for a full week after I forgot to use the right brand of ketchup on his sandwich.

Back then I’d called them quirks. Said he was particular—sensitive. Brilliant in school, polite in public—a model child on paper. But I remembered, too, the way he watched people eat. Watched me. That time I baked cookies with walnuts by mistake and he spit one into the trash, then scrubbed his mouth until his lips were raw. The way he went completely still when disappointed, like he was storing it for later.

A nurse from the hospital called mid‑morning. Ruth’s condition hadn’t improved. They were escalating her case to internal medicine. Still no diagnosis.

No one had mentioned the cookies, and I didn’t volunteer the idea.

I sat in the kitchen waiting for Janelle to call, hands wrapped around a cup of tea I didn’t drink. The mug went cold. The house creaked around me like it was listening. Outside, a UPS truck idled and moved on. Ordinary life kept going, which felt rude.

Ezra had always been good at playing the long game. He didn’t explode like some people. He planned—held things. You could watch him take a slight, file it away, and bring it back sharper later.

When the phone rang just after noon, I jumped.

“It’s Janelle,” she said. “We ran the standard panels. Then I had them go deeper.”

I held my breath.

“There’s something in the cookie,” she said. “Traces of a compound related to aconitum—monk’s‑hood. It’s highly toxic. Rare to find in food. Definitely not an accident.”

I closed my eyes.

“You said someone ate these.”

I couldn’t answer her.

She hesitated. “I’ll write it up quietly.”

After we hung up, I sat still for a long time. My son had sent me something dangerous in a gift box. A box I’d passed on like it was nothing.

Later that evening, I found myself outside again, pacing the front walkway, unsure what I was looking for. The sun was going down. The wind carried the faint scent of cinnamon. Or maybe that was just memory. A neighbor across the street lowered their American flag at dusk.

Then my phone buzzed again. Unknown number. I answered.

“This is Detective Fallon Reyes. Are you Marlene Greaves?”

I hesitated. “Yes.”

“I was referred by Dr. Janelle Morrow. She said you requested toxicology analysis on a food item and asked that any concerning results be passed along to authorities. Is that correct?”

I wanted to say no. To claim some kind of misunderstanding to protect the last shreds of what used to be family. But I heard myself say, “Yes, that’s correct.”

There was a pause—professional, but not unkind.

“Would you be willing to meet to discuss the results and your concerns?”

I agreed, but it felt like signing something permanent.

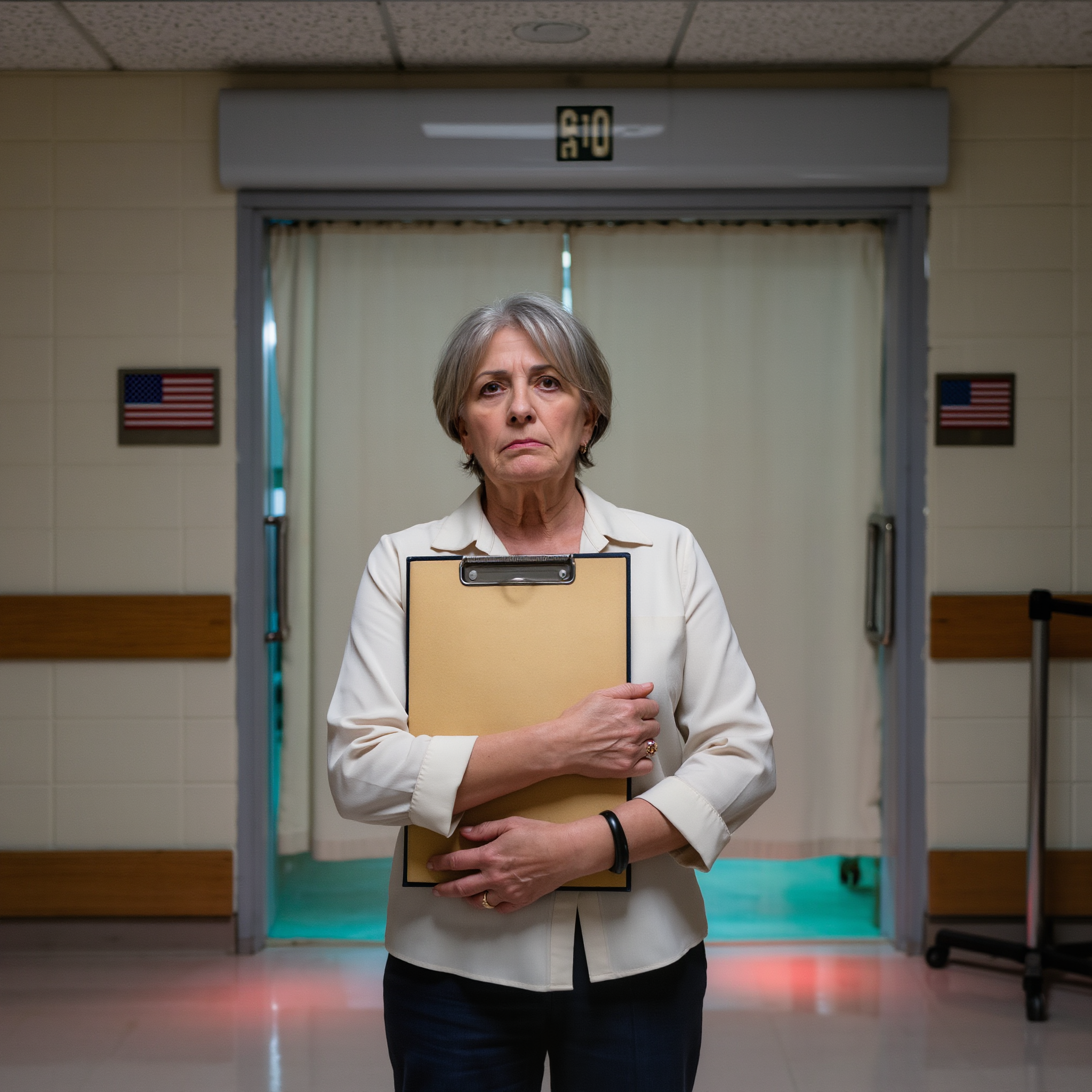

We met that afternoon in a small office tucked behind the police station—American flag by the door, a county map on the wall, a framed certificate from the Ohio Peace Officer Training Academy. Nothing dramatic. Reyes looked young for a detective, maybe mid‑thirties, with sharp eyes that didn’t rest long. He offered me water, which I declined. My hands wouldn’t stop moving, folding and unfolding a tissue I hadn’t realized I brought.

He started soft—asked how long I’d been estranged from Ezra, how often we spoke, when I received the package, what it contained, how Ruth Langford came into the picture. I answered every question plainly, with as much precision as I could manage, avoiding the emotion that kept threatening to surface. He listened closely, jotting notes on a yellow legal pad. He didn’t interrupt.

Then he asked the harder one: “Do you believe your son meant to harm you?”

I looked down at my hands. “I don’t want to believe it,” I said. “But the cookie had something harmful in it. Ruth didn’t bake it. I didn’t bake it. He sent it. And the bottle I found in the trash—it wasn’t mine. The timing fits.”

“Any reason he’d want to harm you? Financial motive? Family tension?”

I flinched. “He resents me. Always has, I think. Blames me for things I couldn’t fix.”

Reyes nodded slightly, but doubt swam in the space between his eyes. All I had was a tainted cookie and a feeling in my gut. No fingerprints, no witness, no confession.

He leaned forward. “Would you be willing to submit the cookie and the bottle as evidence? Let us open a formal case.”

I hesitated. It felt like betrayal, even though I knew better. Even though Ezra had made his move first.

“Yes,” I said finally. “If there’s any chance he’s done this before or would do it again, I can’t ignore that.”

He nodded and stood, signaling the end of the meeting. “We’ll log the items and keep you informed. If anything changes, please call me directly.”

As I walked out of the station, the sky was beginning to darken. I got into my car—locked the doors out of habit—and sat with my hands on the steering wheel. It wasn’t guilt exactly. It was something older, deeper. The knowledge that motherhood doesn’t end just because the child has changed.

The part of me that had once packed Ezra’s school lunches now sat quiet and stunned, trying to understand how the boy I raised became the man who sent me a box of danger wrapped in ribbon.

That night, I didn’t sleep. I left the hall light on. Every creak in the house made me sit up and listen. The refrigerator motor became a countdown I couldn’t turn off.

By morning, I had decided. If he didn’t want me to know what he was capable of, he should have been more careful. I would go see him—not as his mother, but as the woman he underestimated—and I would bring a recorder.

Ezra answered the door with a tight smile, the kind that didn’t reach his eyes. He looked thinner than I remembered, like something inside him had been slowly hollowing out.

“Mom,” he said, stepping aside. “This is a surprise.”

I forced a smile. “I heard about Ruth. I wanted to check in, see how she’s doing.”

He nodded, gesturing me in. “She’s still at St. Luke’s. Laya’s with her. They think it’s some kind of virus.”

I nodded like I believed it. The phone in my coat pocket was already recording.

His kitchen was spotless as always—a place where everything had a place, down to the angle of the knife block. The window over the sink framed a narrow strip of winter sky and the neighbor’s Stars and Stripes.

“I’m sorry we didn’t get to talk more the other day,” I said. “The cookies were lovely.”

Ezra raised an eyebrow. “Were they?”

I watched his face. “I didn’t try them, actually. Ruth was thrilled. She said the star‑shaped one was her favorite.”

There it was—the flicker. Barely a pause, but enough. His eyes narrowed just for a second, and his voice softened.

“Ruth picked the stars.”

I hadn’t said what shape she ate, only that she liked one.

“Yes,” I said slowly. “She mentioned it.”

He turned to the sink, rinsing a glass that didn’t need washing. “She always did go for anything pretty. Always more concerned with how things look than what’s underneath.”

I studied him. “You never told me you’d started baking.”

He laughed, but it sounded off. “New hobby. Good way to unwind.”

“Where’d you learn to use monk’s‑hood?”

He froze—not visibly, not dramatically—but something shifted in his spine. A stillness that told me he was deciding how to react.

“I don’t know what that is,” he said, too quickly.

“Dr. Morrow does.”

He turned the glass still in his hand. “You went to Janelle.”

“She ran the test. It was in the cookie. Ezra, I don’t know what you think you’re doing,” he said, setting the glass down with care, “but accusations like that… they don’t end well—especially without proof.”

“I think you’ve already given me enough,” I said quietly. “You slipped up.”

He stared at me for a long time. His face didn’t move, but something behind his eyes did—a flicker of calculation.

“You’ve always misunderstood me,” he said.

“No,” I said. “I think I finally understand you completely.”

I reached for my purse, keeping my hand steady. My heart was thudding so loudly, I was sure he could hear it.

As I turned to leave, my eyes landed on the counter behind him. There, partially obscured by a tea towel, was another small bottle—identical in shape to the one I’d found in my trash.

Ezra noticed my glance. He moved to block the counter casually, as if stretching.

“I should go,” I said. “I’ve already taken up enough of your time.”

“Give Ruth my best,” he said, voice light again.

I stepped outside into the cold air, every nerve in my body alert. The phone in my coat pocket was still running. I didn’t stop it until I was back in my car—doors locked, engine running.

I sent the audio to Detective Reyes before I could change my mind.

And then I drove straight to St. Luke’s. Ruth was still unconscious. Laya sat beside her, eyes red. I told her what I had to—everything. She didn’t look away. She didn’t argue. Her shoulders sank like she’d been holding up a roof by herself.

By the time I left, the sun had gone down and the sky was heavy.

That night, I slept on the couch with the hallway light on, the phone beside me. I didn’t close my eyes for more than a few minutes at a time. When it rang in the early hours, I didn’t flinch.

Detective Reyes called just after sunrise. The audio was enough. Coupled with the toxicology results in Ruth’s medical report, it gave them the warrant they needed. Ezra was taken in before noon—quiet, composed, like he’d rehearsed it.

I didn’t go down to the station. There was nothing left to say.

Ruth woke slowly over the next few days—confused, then grateful, then silent. I sat with her when Laya couldn’t. She didn’t ask for details, and I didn’t offer them. A muted daytime show played in the visitors’ lounge; a folded newspaper on the table showed a weather map of the Midwest and a tiny U.S. flag in the corner of the masthead.

One afternoon, I took her hand and said, “I’m sorry.”

She squeezed it once. That was enough.

Laya cried in my kitchen later that week. She said she should have known. Ezra had grown distant—strange. She’d found notations in his journals, jars of dried plants she didn’t recognize. She thought he was just coping with… what, she didn’t know. Turns out he’d been writing under a false name on obscure herbal forums for years—descriptions of extractions, dosages, interactions. Academic in tone, chilling in hindsight. Some of the terminology matched exactly what was found in Ruth’s blood work.

It all came back to one decision—one cookie I hadn’t eaten.

I took the container out of the fridge on a quiet Tuesday morning. The cookie was still intact, though the frosting had dulled. Detective Reyes had given me a sealed evidence bag the day Ezra was taken in, in case I wanted to hold on to it—not for revenge, he’d said, but for clarity.

I slid the cookie into the bag and pressed the seal shut. It felt heavier than it should have.

That night, I cleared out a small fireproof box from the hall closet and placed the cookie inside. Alongside it, I added the card from the package:

Happy Birthday, Mom. Let’s start over.

I locked the box and placed it on the highest shelf—not to forget, but to remember what I almost missed.

I stood in the kitchen a long time after that. The house quiet around me, the air still. Outside, a porch light glowed across the street; the flag on my neighbor’s pole barely moved.

Then I turned off the light and walked down the hall, unsure whether to feel safe again—or whether I ever really had.

—

ADDED EXTENDED BEATS (Seamlessly read as part of the same chapter):

On the drive home from St. Luke’s, the sky hung low and pewter. A high‑school marching band practiced somewhere behind the stadium; the snare line rattled like rain on tin. I passed the hardware store with the mural of a bald eagle spread across the brick and a chalkboard sign that read: GOD BLESS AMERICA. OPEN ‘TIL 6. Ordinary life had the nerve to go on.

At a red light, I realized I’d been holding my breath since the first knock on my door. I let it out slow, palms flat on the steering wheel, and watched my breath fog the glass. The wiper left a clean arc, then the mist took it back.

At home, I laid out every card Ezra had ever given me—elementary school crayon drawings, middle‑school printouts trimmed with zigzag scissors, high‑school photo strips from the Fourth of July fair. Little evidence of a boy who once lined up his toy cars by color and hesitated before blowing out candles, wanting them to go in even numbers. None of it explained a ribboned box on my porch.

I called the church kitchen, where I volunteer on Thursdays. “Can I bring soup tomorrow?” I asked out of habit. “Tomato basil. Maybe cornbread.” I needed the normalcy of measuring cups and oven timers, the way a hot tray insists you pay attention to the present moment. I needed something that did not lie.

When I finally slept, it was in slices. I dreamed of sugar stars that wouldn’t melt and a blue pen signing my name over and over, the loops tightening until the letters broke.

Morning brought the practical things—insurance forms, phone calls, a visit from an officer to collect the items properly. He wore a winter jacket with the county seal and took photographs in my kitchen under the humming light. He asked if I wanted a victim advocate to call. I hated the word and took the number anyway.

In the afternoon I drove past Ezra’s subdivision. American flags clipped to mailboxes, a Little Free Library with a laminated flyer for a neighborhood watch meeting, cul‑de‑sacs named after trees that had been cut down to pave them. I circled once, twice, three times—then kept going. I had promised myself I would not knock on that door again without a reason that felt like mercy.

Ruth’s first full sentence after she woke was about the wind chimes. “They’ll tangle if we don’t take them down for winter,” she murmured. Laya laughed and cried at the same time, and I squeezed Ruth’s hand until she squeezed back. The monitor beeped steady. No sugar stars, no blue ribbon, just the factual mercy of numbers marching in order.

A week later, Detective Reyes called to say there would be a hearing. I sat on the wooden bench behind the rail and studied the seal of the State of Ohio carved above the judge’s head. Nobody said the word I feared. We said “substance” and “compound” and “ingestion” and “toxicity,” and the language itself became a shield that kept the worst part from looking me in the eye. When it was my turn, I spoke carefully, like stepping across a creek on winter stones. I told the truth and did not add adjectives.

Outside the courthouse, a winter flag cracked in the wind. Reyes stood with his hands in his coat pockets and watched it a moment. “You did the hard part,” he said. “The rest is paper and patience.”

Paper and patience. I took the phrase home and set it on my table like a vase.

That night, I opened the fireproof box and read the card again. Let’s start over. The letters were neat, unblotted. I traced the words without touching them, as if warmth could make ink confess what it meant. Then I slid the card back into its sleeve and closed the lid.

I baked a sheet of plain sugar cookies—no icing, no stars. I took half to the church kitchen and left the rest on Ruth’s counter beside her wind chimes, now wrapped for winter with a ribbon of red, white, and blue. When she asked if they were safe, I said, “Yes,” and this time the word didn’t wobble.

On Sunday, I sat on the porch swing with a fresh crossword and a cup of coffee that stayed hot to the bottom. The lawn still refused to be green, but the light across it was honest. The mail carrier waved. Somewhere in the distance, a stadium played the national anthem before the game. I stood, hand over my heart, not out of habit but because a quiet part of me was still here—standing—after everything.

The box on my shelf stayed shut. The house breathed. And when the phone rang, I let it ring once, twice, three times before I answered—long enough to remember that starting over, if it ever comes, should feel like light through a clean window, not like a knock in the dark.

—

ADDED EXTENDED BEATS II (Police Station • Church Kitchen • Neighborhood HOA):

POLICE STATION — CHAIN OF CUSTODY

Detective Reyes called the next morning to finalize something he called “chain of custody.” I met him at the station’s back entrance, where delivery trucks idled and a salt crust clung to the asphalt. Inside, the evidence clerk buzzed us through two doors—each one thunking shut behind us with civic finality.

A laminated poster on the wall read: PROPERTY • EVIDENCE — FOLLOW THE STEPS. Below it, a list as spare as a recipe card.

- Item received.

- Item logged.

- Item sealed.

- Item signed.

“Everything in criminal court,” Reyes said, “lives or dies on these four lines.”

He set the evidence bag with my cookie on a stainless‑steel counter beneath a fluorescent light that made sugar look like frost. The clerk wore purple nitrile gloves and scanned the barcode with a beep that felt louder than it was. We checked lot numbers, signatures, dates, the lab control number Janelle had generated. My name was written once, then again. REYES, F. signed under mine with the kind of careful penmanship that belongs to people who know exactly where a mistake will get you.

“Do I keep a copy?” I asked.

The clerk slid a carbon sheet toward me. “White for you, yellow for records, pink for court.”

Pink for court. I folded it once, twice, then flattened it back out. “If this goes to trial,” I said, “will they show… the cookie?”

“Probably not. But the bag matters. The path it took matters.” Reyes tilted his head toward the poster. “The paper is the proof that the truth didn’t get lost.”

In the hallway, a school tour shuffled past—kids in puffy jackets, eyes wide at the badge display. One of them glanced at the clear bag in my hand and then up at me. I tucked it closer to my chest without thinking.

“Paper and patience,” Reyes said when we reached the door. “You’re doing both.”

CHURCH KITCHEN — POTS, LADLES, MERCY

Thursday afternoon brought steam and stainless steel and the kind of noise that forgives you for not having the right words. The church kitchen smelled like onions, basil, and lemon cleaner. I tied on an apron that said HOPE STARTS WITH A SPOON and set a stockpot to simmer.

“Greaves, you’re early,” called Mrs. Bell, queen of the pantry. “We got donations from Kroger—watch for the dented cans.”

I smiled. “Tomato basil. Cornbread in forty.”

“You look like you slept in a question mark,” she said, sliding a cutting board my way.

“Court things,” I said. “Paper and patience.”

“Sugar and salt,” she countered. “Life needs both.”

We worked without filling the quiet too much. I chopped; she stirred. A teenage volunteer in an OSU hoodie labeled takeout clamshells with a black Sharpie: BEEF STEW, VEGAN, GLUTEN FREE. Outside, a line had already started—grandfathers with baseball caps, mothers balancing toddlers on hips, a high‑schooler wearing a varsity jacket and embarrassment. Hunger is a remarkable equalizer; shame is not.

“Miss Marlene?” the kid in the hoodie said. “Do you ever write down your soup recipe?”

“It’s more like a method,” I said, and told him: sweat onions slow, add garlic late so it doesn’t burn, use a splash of vinegar to wake the pot, finish with a pat of butter for shine. He typed it into his phone as if he were copying a law.

“Who taught you?” he asked.

“My mother,” I said, “and every person who ever handed me a wooden spoon when I needed something to hold.”

We packed trays—two dozen, then three. Mrs. Bell slid a pan of cornbread onto the counter, golden at the edges, honest in the middle. I pressed a warm square into my own palm and let it sit there like proof that heat can turn batter into something you can actually carry.

In the quiet moment between batches, I texted Laya: Soup on your porch. Ringing once and running. She sent back a heart and a thank‑you and an update: “Ruth asked about the wind chimes again. We told her we wrapped them with the winter ribbon. She smiled with her eyes.”

NEIGHBORHOOD HOA — EARS, FLAGS, WHISPERS

On Saturday, the HOA posted about a “Community Safety Conversation” at the clubhouse. I hadn’t been inside since the Fourth of July potluck, when Ezra had once manned the grill with surgical precision, flipping hot dogs at exactly ninety seconds per side.

The room smelled like coffee and lemon sanitizer. Folding chairs in rows, a podium with a tiny brass eagle. On the back wall, a corkboard carried lost‑dog flyers and a faded announcement for an American flag retirement ceremony. Neighbors filed in with the same faces they wore at yard sales and bake‑offs. Concern looks the same in most zip codes; judgment only needs a nudge.

“Miss Greaves,” said Mr. Patterson from three doors down, the man who measured grass height with a ruler and meant it kindly until he didn’t. “You alright?”

“I’m here,” I said.

“That boy of yours,” he began.

“Is an adult,” I said evenly. “And I’m cooperating with authorities.”

He nodded too many times, then stared at the floor. “You need anything, you holler.”

At the podium, the HOA president cleared his throat. “We’ve all heard rumors. Let’s keep this factual. The sheriff’s office has assured us there’s no ongoing threat to the community.” He gestured toward the flag in the corner. “We support our neighbors. We fly our flags. We mind our business until asked.”

Hands rose. Someone asked if the clubhouse kitchen could install cameras. Someone else wanted a sign‑in sheet for deliveries. A woman in a denim jacket said, gently, “Maybe we just need to know each other better than we know each other’s rumors.”

When it was over, I lingered by the flyer about the flag retirement. A girl of about ten stood beside me, clutching a worn‑out banner folded the wrong way. “It touched the ground,” she said, eyes wet.

“We can fix the fold,” I said, and showed her the triangle pattern my father taught me on our porch—a habit as American as any court seal. Fold over, then up, tuck the red safely inside the white.

On my way out, the president stopped me. “You don’t owe anyone here an explanation,” he said. “But if you ever want to use this room—for support, for silence—say the word.”

“Support or silence,” I said. “Maybe both.”

CLOSING THE LOOP — A QUIET YES

That evening the sky went lavender. I drove to Laya’s, set a paper bag on the porch, and rang once. Inside: two quarts of soup, four squares of cornbread, and a small envelope with a note: WIND CHIMES IN SPRING. I didn’t wait for the door. Good help respects a threshold.

At home, I opened the fireproof box again. The card waited, neat as ever. I didn’t trace it this time. I read it once and put it down, then took out a sheet of printer paper and wrote, in my own hand, in blue ink: PAPER AND PATIENCE. I folded it into a triangle—old habit—and set it beside the card.

When the game started across town, the anthem rose and fell like a tide. I stood again, because standing felt like agreement with the world’s insistence on continuing. Then I sat, sipped a cup of coffee that tasted like coffee, and watched the porch light wash the steps in a simple, American kind of mercy.

Somewhere, a wind chime ticked against its winter ribbon. Somewhere, in a climate‑controlled room, a clear bag with a cookie sat behind a lock, name and date and number lined up in a way that would make sense to strangers. And here, in my kitchen, the air didn’t lie. It smelled like basil and soap and cornbread cooling on a rack.

When the phone rang, I let it go to voicemail. Then I pressed play and said, “I’ll call you back when the coffee’s done.”

I meant it. And the quiet that followed felt like a beginning that didn’t need a ribbon to prove it.