Westbrook High, New Jersey — third period, Algebra II.

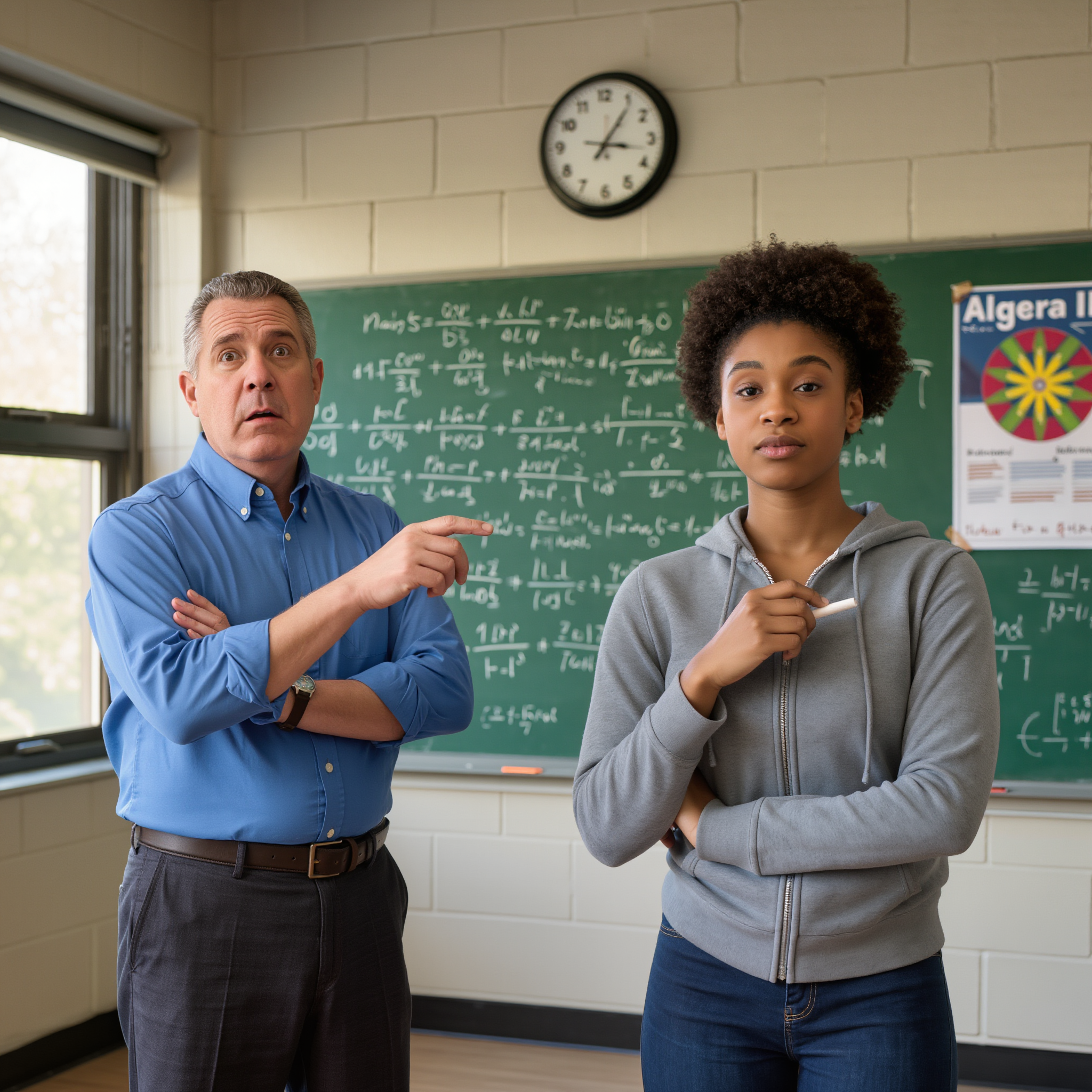

The classroom was silent except for the sound of chalk whispering over the board. Fluorescent lights hummed faintly above rows of laminate desks; outside the tall windows, a flag on the yard pole hung limp in the late‑morning air. Mr. Reynolds — a strict, famously condescending math teacher whose tie knots were as tight as his smile — turned around, his smirk widening as he eyed Maya, the quiet girl sitting in the back row by the radiator.

“Since you seem so uninterested in class,” he said, tapping the chalk once against the slate, “why don’t you come up here and solve this.”

He stepped aside, revealing a layered equation that even the brightest students struggled with — exponents nested inside fractions, variables braided through radicals, a tangle of parentheses meant to trap the unwary.

Maya hesitated.

She wasn’t uninterested. She was used to being ignored. She kept her notebooks neat, her hand down, her head low. Her hands clenched into fists under the desk; a tautness pulled across her stomach. Plastic chairs squeaked as the entire class turned. Some students snickered. Others bent toward one another to whisper, the way people do when they think they already know the ending.

“Come on, don’t be shy,” Mr. Reynolds taunted lightly. “Or are numbers too difficult for you?”

A couple of kids laughed. It wasn’t loud — more like a nudge, a social cue: play along.

Maya’s heart pounded. She knew exactly what this was. He didn’t expect her to solve it; he wanted her to fail in public, to make a point about attention and effort, to remind everyone who owned the front of the room.

She took a breath. Then another. She stood.

With slow, deliberate steps, she walked to the board. The equation loomed larger up close, crowded with symbols that looked like they’d been thrown there in a storm. She could feel the weight of every eye on her shoulders.

Mr. Reynolds crossed his arms. “Go ahead. We don’t have all day.”

Maya picked up the chalk. It was small, used to a nub, leaving a ghost on her fingertips. The truth was, she had always loved math. Numbers made sense in a way people didn’t. Numbers listened, if you knew how to speak their language. But she’d never been given the chance to prove it here — not in this room with its laminated posters about growth mindset and a teacher who used those words like decorations.

The moment the chalk touched the board, the room inhaled.

She did not hesitate. She began by isolating structure, not numbers: factor the numerator, rationalize what could be rationalized later, simplify the spine before you touch the skin. One step at a time, she broke the problem into manageable stone and moved each piece. Her movements were confident, precise. The snickers faded. The whispers thinned and vanished.

Mr. Reynolds’s smirk twitched.

By the time she reached the final line, the room was silent enough to hear the HVAC sigh. She underlined the answer once — not a flourish, just a period — and put the chalk in the tray. She turned to face the class.

“Was that all?” she said, voice steady.

Mr. Reynolds blinked. His mouth opened and closed. A soundless fish at the surface. He had set her up to fail, but instead, he had just made the biggest mistake of his year.

The silence stretched. He stepped closer to the board, scanning her work. There had to be a mistake. There always was. Quiet students were quiet for a reason, right? A mind like this could not have been sitting in the back row all semester.

But the numbers didn’t lie.

A brittle chuckle escaped him. “Well… lucky guess,” he muttered, reaching for the eraser. “Let’s try another one.”

Maya crossed her arms. “There’s no luck in math, sir. It’s either right or wrong. And that — ” she tipped her chin to the board — “is right.”

The class erupted into the sound people make when the script changes. A few gasps, a smatter of laughs, an electricity skittering along the desktop edges.

Jason, a boy in the front row in a varsity hoodie, leaned forward. “Wait — hold up. That was actually right?”

Before Mr. Reynolds could answer, another voice cut through the tension.

“That was more than right.”

It didn’t belong to a student. At the doorway, a tall man in a sharp gray suit stood with his arms crossed. His expression was neutral, but his eyes were fixed on the board — then on Maya.

Mr. Reynolds stiffened. “P–Professor Carter,” he stammered. “I… didn’t realize you’d arrived.”

Maya frowned. “Who?”

The man stepped into the room, polished shoes clicking against the tile. “I came to discuss the upcoming academic competition,” he said, “but now I’m far more interested in this.” He gestured toward the board. “Tell me, young lady, do you often solve equations like these?”

Maya’s fingers tightened on the hem of her sweater. “I… just like numbers,” she said.

The professor studied her for a beat, then turned to Mr. Reynolds. “And you thought she couldn’t do it?”

Mr. Reynolds looked cornered. “She’s never… spoken up in class. I had no idea—”

“That’s because you never asked,” Professor Carter said, almost gently, and then turned back to Maya. “How would you like to take a real test — one that might change your life?”

Maya’s breath caught. The class held theirs. Mr. Reynolds’s face went a shade paler. He had intended to embarrass her; instead, he had opened a door he didn’t know was there.

“A real test?” she asked. “What does that mean?”

“The kind that isn’t about proving your worth to a single teacher,” he said, eyes warm, “but to the world.”

Desks creaked as students shifted. Jason whispered, “Yo, what is happening right now?” The word “scholarship” darted through the room like a bright fish.

“I’m a recruiter for the National Mathematics Scholars Program,” the man explained. “We search the country for students with extraordinary ability who haven’t had the right opportunities yet.” He tapped the first line of the problem. “This was not meant for high school. It’s from a first‑year graduate qualifying set. You solved it in minutes.”

Maya swallowed. She knew she was good. But special? Numbers were a place to breathe, not a stage. Now the lights felt hotter.

“With all respect,” Mr. Reynolds said, jaw taut, “I don’t think she’s ready for something like this.”

“She’s exactly the kind of student we’re looking for,” Professor Carter said. His voice was calm, but there was steel in it. “Whether or not you saw her potential is irrelevant.”

Heat stung Maya’s eyes — not from shame this time, but something like relief, like a door finally unlatched.

Professor Carter took a card from his pocket and set it on her desk. Thick stock, raised lettering. “Placement exam. Next week. If you pass, you’ll be eligible for a scholarship to one of the top universities in the country.”

The room buzzed. The future clicked into a new gear.

Mr. Reynolds cleared his throat. “Maya, I’m sure you’ll need time to think—”

“No,” she said, surprising herself with how steady it sounded. “I’ll do it.”

Professor Carter smiled. “Good choice.”

Mr. Reynolds looked like he’d bitten into a lemon slice by mistake.

Maya slipped the card into the front pocket of her notebook — as if proximity could make it real — and for the first time since freshman year, the back row didn’t feel like a hiding place. It felt like a launch pad.

—

The bell rang, but no one moved. Conversations broke out in tight pockets. Phones appeared like periscopes.

As the room emptied, Professor Carter offered a quick nod. “I’ll email your counselor the details.”

“My… counselor?” Maya said.

“Ms. Patel,” he replied without looking at his notes. “I’ve heard she fights for her students.”

She did. Ms. Patel was the kind of guidance counselor who kept granola bars in her desk and statistics in her head. She met students where they were and talked to them like they could be anything. She once slid a brochure toward Maya for a summer coding camp; Maya had said she couldn’t because of work. Ms. Patel hadn’t pushed — but she’d circled the financial aid section in purple.

Maya stepped into the corridor, the smell of disinfectant and pencil shavings. Jason jogged to catch up.

“Yo, Maya, that was insane,” he said. “You really showed him.”

Another student chimed in. “I had no idea you were this… you know. Good.”

“Neither did I,” Maya said, and it was true in some way. Not because she lacked the ability — but because she’d never been allowed to imagine the scale of it.

By lunch, the story had mutated the way stories do. “She solved a PhD thing in five minutes.” “MIT is coming to get her.” “The principal is making the teacher apologize over the intercom.” None of those were true — not yet.

On her tray: apple, milk, slice of pizza. In her pocket: a card. In her chest: a small, hot comet.

—

That night, in their small apartment above a laundromat on Maple Avenue, Maya spread practice problems across the kitchen table. The place was warm; steam rose from the dryer vents downstairs and fogged the window glass. The neon OPEN sign blinked, casting gentle pulses on the ceiling.

Her mother stood in the doorway, arms crossed in a way that was more protective than skeptical. “You’ve been pushing yourself hard,” she said softly. “I’m proud of you. But breathe, okay?”

“Just one more problem, Mama.”

Her mom smiled. “You always say that.” She set a mug of tea beside the spiral notebook. “Mr. Reynolds will learn what I already know.”

“What’s that?”

“That you don’t talk to numbers,” her mother said, tapping the page. “They talk to you.”

Maya laughed under her breath. “It’s not like that.”

“Maybe not,” her mother said. “But I hear you in here at midnight, whispering proofs.”

Proofs. The word felt like a promise.

—

The week moved like a city train: fast, loud, skipping some stops, slowing unexpectedly at others.

Ms. Patel tracked her down between classes. “I got an email,” she said, a glint in her eye. “And I printed it twice in case the first one catches fire from excitement.” She handed over a small packet — logistics for the placement exam, a non‑disclosure statement, a schedule. “We’ll set up a quiet room. I’ll proctor. You’ll do your part; I’ll do mine.”

“Thank you,” Maya said. The words sounded too small.

In Algebra II, Mr. Reynolds dialed down the sarcasm and dialed up the professionalism, like a radio host switching scripts after a caller complained. He didn’t mention the board incident. He did, however, start cold‑calling other students who sat in back rows.

Jason slipped her a folded paper during study hall: a link to an online problem set known to brutalize honor students and healers of honor students. Underneath, he’d drawn a tiny rocket.

At home, Maya worked until the numbers blurred. She practiced not just technique but stamina — the length of attention it takes to walk through a forest and remember where you started. She learned where she lost speed. She learned how to get it back.

Her mother took a second shift for the week so the apartment would be quiet in the evenings. “This is me helping,” she said when Maya protested. “Someday, you’ll help me back with stories from a stage I’ve never seen.”

On Thursday, the laundromat’s neon light flickered out. The room went darker, cozier. Maya solved by lamplight, the city a hush outside.

On Friday, fear visited. It sat on the edge of the chair and swung its feet. What if I’m only good at classroom problems? What if the real thing is bigger than me? She wrote the questions down and answered them the only way she knew how: with an example, with a line, with an equal sign.

—

Monday arrived dressed like a test: sky the color of lined paper, air that smelled like pencils. The whole school seemed to know. Not because anyone had announced it, but because teenagers can hear gossip through walls.

The exam wouldn’t be public, but the building swelled with the energy of a game day. Teachers pretended not to notice. The principal did notice and wore his best neutral expression.

The designated room was the small conference space off the library — carpeted, glass‑walled, with a view of maple trees and a mural about reading. Ms. Patel had arranged two sharpened pencils parallel to each other, a fresh whiteboard marker, a bottle of water, and a bowl of peppermint candies like a hotel check‑in desk.

Professor Carter arrived exactly on time. He carried a thin leather folder and a kindness that didn’t condescend. He shook Maya’s hand as if she were a colleague.

“Ready?” he asked.

“No,” she said honestly. “But yes.”

“That’s about right,” he said, and smiled.

He explained the rules: timed sections; one open‑ended proof; one problem that might not be fully solvable but would be a map of her thinking. “It isn’t about speed alone,” he said. “It’s about how you build.”

Maya nodded. She had been building all week.

The clock started.

For the first ten minutes, her heartbeat was the loudest thing in the room. Then the math took over. Structure first, then detail. Define the moving parts, set constraints, look for invariants, choose the right tool. She forgot to be seen. She remembered to be herself.

In the middle section, a combinatorics problem threatened to eat an hour. She caught herself chasing a path that looped back on itself, smiled, and drew a line through it. Start again from the hinge. Things clicked. The sound of Ms. Patel’s keyboard in the corner became friendly static.

When it was over, she felt the kind of tired that means you gave exactly what was asked.

“How do you feel?” Ms. Patel asked quietly, like a nurse after a difficult procedure.

“Like I told the truth,” Maya said.

Professor Carter stacked the pages, eyes moving quickly, eyebrows lifting at intervals. He didn’t comment. He didn’t need to; his face already had.

“We’ll be in touch very soon,” he said. “But before I go — would you be willing to walk through one of your solutions on a whiteboard for a few teachers who are… curious?”

“Curious,” Ms. Patel repeated, smiling with only her eyes.

Maya glanced through the glass and saw the gathering outside: the principal, a couple of math teachers, a cluster of students trying not to look like a cluster of students. Mr. Reynolds stood at the back, arms folded. A camera phone hovered at hip height.

“If you don’t want to, you don’t have to,” Ms. Patel said.

Maya looked at the whiteboard, then at the hallway. She didn’t feel like a spectacle. She felt like a person who had something to say.

“I’ll do it,” she said.

—

They moved to the largest classroom near the library. Someone had wheeled in a standing whiteboard. Desks filled quickly. Even the principal took a seat. The head custodian poked his head in as if checking ventilation and stayed for the show.

Mr. Reynolds stood near the windows, that tight neutral expression teachers use when they’ve been told to attend a workshop they didn’t ask for.

“This equation,” he announced, projecting to the back row, “has stumped advanced students for years. Even graduate students struggle with it. But Maya here believes she’s capable. Let’s see if she is.”

He uncapped a marker with a little too much flourish and wrote a monstrous expression. It wasn’t exactly the same as last week’s; it was nastier in the places people couldn’t see at first glance. A good trap looks like a fair fight.

A hush fell.

Maya stepped forward. The marker felt heavier than chalk, but her hand steadied. For a second, the noise of the room threatened to flood her. She thought of her mother’s voice — breathe, baby — and the fear faded like a tide.

Focus.

Where most people saw a wall, she saw seams. The trick in the numerator was an illusion designed to pull you into expanding chaos; the only winning move was to look the other way, to frame the problem as a limit and let the messy parts simplify themselves. She changed variables, set a boundary, looked for the invariant that polite problems hide and rude problems flaunt.

The first line was deliberate. The second quicker. Then the third, fourth. She wrote the way a runner runs when their breathing and stride lock into rhythm — not fast for speed’s sake, but with efficiency that looks like grace.

Whispers bubbled then went still. Someone dropped a pen. Someone else didn’t pick it up.

Mr. Reynolds’s smirk began to falter, then sag.

Professor Carter leaned forward, forearms on his knees, eyes bright.

Maya capped the marker and set it gently in the tray.

Silence.

The answer sat there, clean and undeniable.

A gasp shot through the room like a spark on dry leaves. Then chaos: chairs scraped, phones angled, a “No way” from the back, someone whisper‑shouting “She did it.”

Professor Carter stood first. He ran a hand through his hair, a surprised laugh escaping. “That’s…” He shook his head. “That’s correct.”

Maya turned. Mr. Reynolds’s face had gone pale. He opened his mouth, closed it. The air around him seemed to thin.

For one strange second the whole room froze, like a paused video. The only sound was the marker rolling slowly along the tray until it clicked against the edge.

Then the noise returned all at once.

Students buzzed with the particular joy of watching a story where the underestimated character wins. The principal clapped twice, awkwardly, like a man who wasn’t sure if this was a pep rally or a deposition. The custodian grinned, wide and honest.

“It’s just—” Mr. Reynolds tried, reaching for an excuse mid‑air. But the weight of the moment bent his words out of shape.

Maya met his gaze. Calm. Unwavering. “What was it you said the other day?” she asked softly. “That I didn’t belong in your class?”

He swallowed. Pride is a thick thing to get past. An apology tried to form and failed to find air.

Professor Carter placed a hand on Maya’s shoulder. “We need to talk after,” he said warmly. “I have colleagues at MIT who would be very interested in meeting you. And Harvard. And Stanford.” He said the names the way a coach says positions, not trophies.

Mr. Reynolds flinched like the light was too bright.

Maya’s pulse hammered. Doors she’d never dared to approach were opening like they’d been motion‑activated the whole time.

She picked up her backpack. At the doorway, she paused and glanced back.

“I guess I do belong here after all,” she said.

Then she stepped into the corridor.

—

In the days that followed, life did not transform into a movie. It shifted the way real life shifts when something true has been said out loud: subtly at first, then obviously, then permanently.

In first period English, the teacher asked a question about theme and, for the first time, Maya let her hand rise on instinct. In chemistry, a lab partner asked what she thought before doing the thing anyway, then doubled back and did it Maya’s way. In the cafeteria, tables that had never noticed her made space.

Ms. Patel walked by with a thumbs‑up that said more than a sentence could. The principal emailed her mother. Her mother printed the email and taped it to the fridge like a certificate.

Professor Carter followed through. He connected Maya with a Saturday problem‑solving circle on Zoom where kids from Chicago and Atlanta and Boise shared screens and strategies like trading cards. He sent three articles that were too hard on purpose. “Skim for structure,” he wrote. “Ignore the scary words.”

One quiet afternoon, the door of Algebra II clicked shut behind Mr. Reynolds a little more softly than usual. He straightened a stack of quizzes that didn’t need straightening and said, “Class, I want to acknowledge something. When we talk about potential, we must be careful not to mistake quiet for absence. That’s all.”

It wasn’t an apology. But it was the first true sentence he had offered the room all year.

—

On a bright Saturday in April, Maya and her mother took the bus to Princeton for a regional event connected to the Scholars Program. The campus was all brick and blossoms; students in hoodies carried iced coffees the size of small planters. In a lecture hall, a woman with gray hair and an easy laugh told a story about failing three times and then writing a paper that changed the way engineers build bridges. Failure is a lab, she said. Not a label.

Maya wrote that down and drew a rectangle around it.

At lunch, she met a kid who could factor polynomials in his head and another who played cello like she was telling secrets to the wood. They all felt oddly familiar: the same brightness, the same tendency to look at the floor when praised, the same relief at finding a room where nobody flinched at the word “proof.”

On the ride home, her mother dozed against the window. The bus hummed. Maya took the card from her wallet and ran her thumb along the raised letters. They didn’t feel foreign anymore. They felt like a promise she was allowed to keep.

—

Weeks later, the official envelope arrived — thick, with a crest that looked expensive just to print. Scholarship. Summer program. Mentorship. A campus visit to Boston in July.

Her mother cried the silent kind of happy that people cry when fear finally loosens its grip. The laundromat downstairs clanged and churned, indifferent and faithful.

Maya walked to the window and looked out at the flag on the pole by Westbrook High. It lifted in a light breeze. She thought of the board, the chalk, the marker in the rolling tray. She thought of Mr. Reynolds’s smirk and the way it had collapsed under the weight of evidence. She thought of Ms. Patel’s granola bars and Professor Carter’s steady voice. She thought of how a life can turn on the axis of one ordinary school day in New Jersey.

Her phone buzzed.

Jason: Yo genius. We saved you a seat at lunch. Don’t make us look bad by doing integrals for fun.

She laughed and wrote back: Coming. No promises.

Then she set the envelope on the table and sat down to do what she had always done, what she would do at any university, in any city, at any chalkboard or tablet or scrap of paper: she picked up a pen, and she began.

—

EPILOGUE (One Year Later)

A poster hung in the Westbrook High hallway: NATIONAL MATHEMATICS SCHOLARS — CONGRATULATIONS MAYA S. Under it, someone had scrawled in marker, You were always this. We just finally saw it.

Mr. Reynolds paused by the poster between classes. He adjusted his tie and considered the sum of the year. In his classroom, a new seating chart sat on his desk — alphabetical, unassuming — and a sticky note on his monitor read in Ms. Patel’s handwriting: Ask first. Assume less.

He nodded once, almost to himself, and turned to the board. The chalk felt lighter than it used to.

Across the state line, in a dorm room with a view of river water and red brick, Maya pinned her mother’s note above her desk — the one that said, simply, You build. I’m watching. — and opened a fresh notebook to the first page.

Numbers do not love you back. They do something better. They tell the truth when you ask the right question.

She smiled.

And asked another.